Democracy is a fundamental human right, as explained by Frank (1992), and cannot be denied under any circumstances. It is also desirable for developmental outcomes since it empowers citizens and makes governments accountable. Therefore, researchers have found evidence (Gerring et al. 2012; Gerring 2022) showing the positive association between democracy and human well-being. The same goes for economic freedom, which is also an inherent human right and desirable for developmental outcomes. Research by Hall and Lawson (2014) indicates that economic freedom is positively associated with desirable social and economic outcomes such as growth, living standards, and happiness. In this blog, I will explore the development of political and economic freedom in South Asian nations, assessing their current state and evolutionary trends.

It is essential to consider the region as a whole in the political economy literature because countries tend to be influenced by their neighbouring countries in terms of their institutional development. One reason for this is the spillover effect: when a country transitions to democracy, it can inspire similar movements in neighbouring countries. For instance, the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 led to a wave of democratization across Eastern Europe. Another reason is the diffusion of norms; democratic norms and values can spread across borders. When neighbouring countries observe successful democratic practices, they may adopt similar institutions, laws, and electoral processes. Additionally, stable democracies contribute to regional security and stability. Cooperation among democratic neighbours can lead to peacebuilding efforts and democratic development. The same is true for economic freedom, as it also has a spillover effect, diffuses norms, and encourages political and economic cooperation. Europe demonstrates the impact of democracy and strong economic institutions in the region, while the Middle East reflects the influence of authoritarian governance on member states. Therefore, examining the regional influence of political and economic institutions in South Asian countries is helpful.

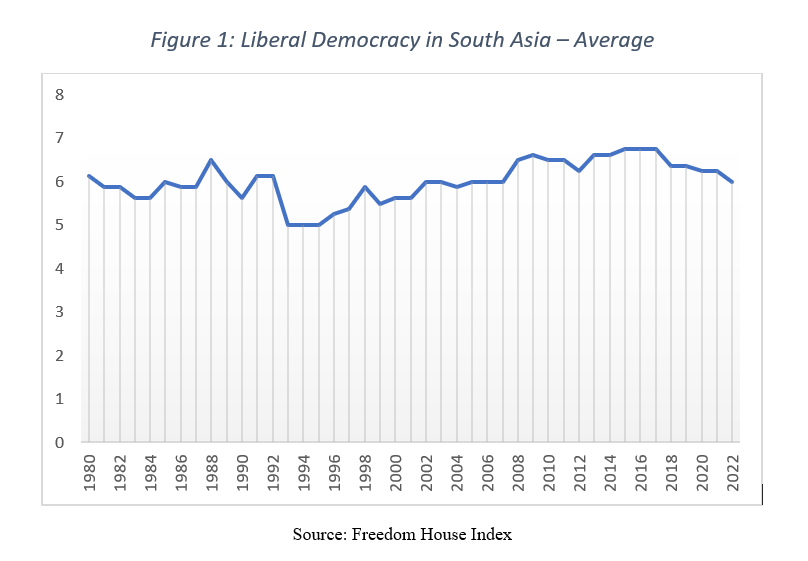

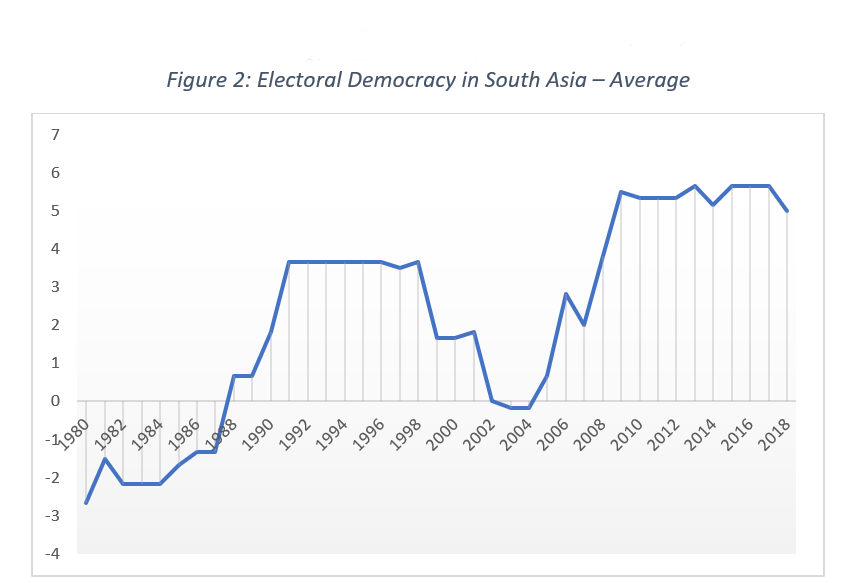

Regrettably, South Asia has not seen the widespread development of democracy as a region. With the exception of India, no other country has achieved the status of a consolidated democracy. Even in India, the level of liberal democracy, as indicated by the Freedom House index, is on a downward trend (see Figure 2). Figures 1 and 2, based on two widely used data sources-Polity2 for electoral democracy and the Freedom House Index for liberal democracy-depict the level of democratic development in the region.[1]

Data Source: Polity2

(Note: The average method is utilised to calculate the democracy level. In Average, Afghanistan is not included because of inconsistency of data and Maldives data is not available)

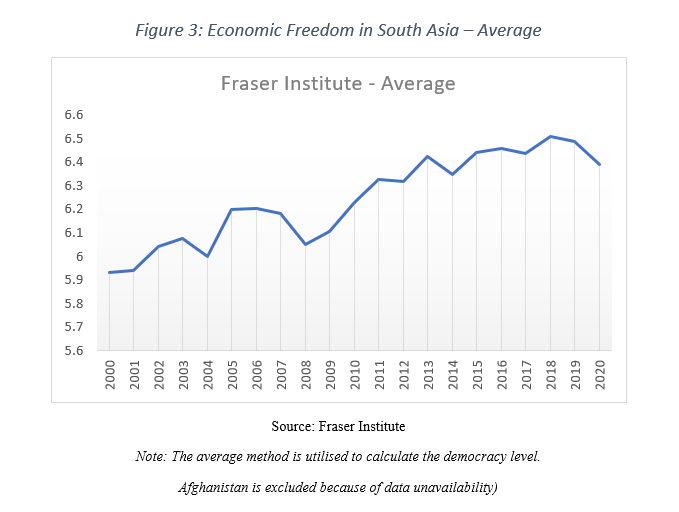

Figure 3 shows a slight increase in the level of economic freedom. In 2000, the level was around 6; after 20 years, it increased by just 0.4 points. It is important to note that the maximum value of the Fraser Institute index is 10, which represents the overall strength of economic institutions. This suggests that economic institutions in South Asia are not making significant progress over time; they are stagnant. Their level of development remains lower than the maximum value of 10.

Before 1988, the average level of electoral democracy in South Asia was negative, indicating an overall authoritarian political nature in the region. However, between 1990 and 1998, democracy began to develop, but it declined again. Fortunately, after 2004, the region regained its democratic position. However, its maximum level is still less than 6, indicating the region’s hybrid nature in terms of democracy, given that consolidated democracy typically starts at a level of 8. The level of liberal democracy appears to be stable. The highest score in the Freedom House index is 14. South Asia as a region has achieved a maximum score of less than 7, further indicating the hybrid nature of liberal elements within its democracy.

By examining these indicators, it’s evident that the region’s level of political and economic freedom falls somewhere in the middle. This suggests a hybrid nature of institutions[2] that may not be conducive to producing economic growth and social development in the area. Consequently, the region is not economically developed.

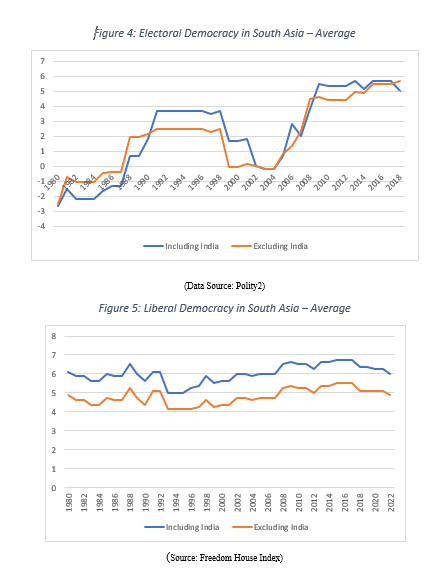

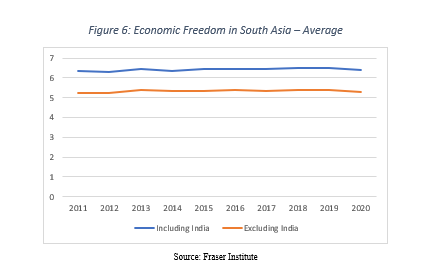

Moreover, the data suggests that India is an outlier in the region in terms of its political and economic freedoms. If we remove India from these indices, the region experiences a significant decline in its institutional development level. This phenomenon is illustrated in Figures 4, 5, and 6 when India is both included and excluded.

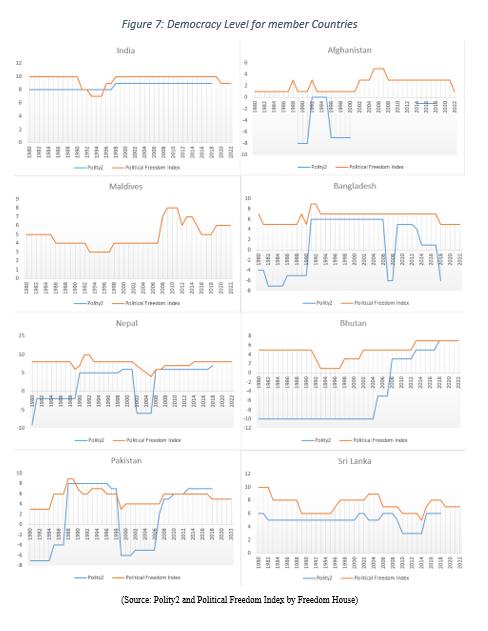

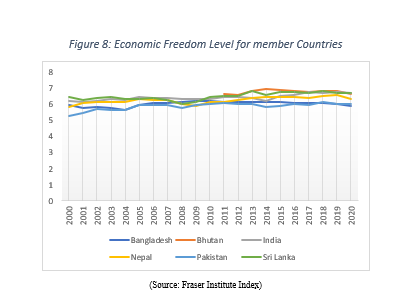

Even when we analyze the South Asian nations individually (as shown in Figure 7), each country has different levels of political institutions. However, there are similarities among them in terms of economic freedom levels (Figure 8), which is surprising. This suggests that regionalization exists in South Asia when considering economic freedom, but not when considering political freedom.

In sum, this blog explores the democracy and economic freedom level in South Asia, given that both freedoms are strong determinants of development and prosperity in the region. It shows that South Asia, as a region, is stuck in the middle (hybrid) level of political and economic freedoms. Moreover, India seems an outlier; dropping India from the sample makes the region poorer in terms of institutional development. Additionally, it identifies differences in democratic development levels among South Asian nations, but also observes similarities in economic institutions across the region.

References:

Franck, T. M. (1992). The emerging right to democratic governance. American Journal of International Law, 86(1), 46-91.

Gerring, J., Knutsen, C.H. and Berge, J., 2022. Does democracy matter?. Annual Review of Political Science, 25(1), pp.357-375.

Gerring, J., Thacker, S.C. and Alfaro, R., 2012. Democracy and human development. The journal of politics, 74(1), pp.1-17.

Hall, J. C., & Lawson, R. A. (2014). Economic freedom of the world: An accounting of the literature. Contemporary economic policy, 32(1), 1-19.

[1] Polity2 is an electoral democracy indicator that consists of six component measures. These measures assess the competitiveness of political participation, constraints on executive power, and openness of recruitment to political offices. The Freedom House indicator, a measure of liberal democracy, includes political rights and civil liberties. Political rights encompass the electoral process, political pluralism and participation, the functioning of government, and political culture. Civil liberties cover freedom of expression and belief, freedom of assembly and association, rule of law, personal autonomy, and individual rights.

[2] Hybrid regimes, also known as mixed regimes, combine features of autocracy and democracy. In the case of economic freedom, they exist in the middle level.