Amidst the excitement and hope of a new life, pre-migrators can experience conflicting emotions, stress and the emotional toll of leaving familiarity behind, shaping journeys long before embarkment. The pre-migration stage is critical in encompassing various preparatory actions and adaptations, with migrants experiencing challenging decision-making processes influenced by socio-cultural dynamics. While logistics often dominate the focus, South Asian migrants can face significant psychosocial challenges in the months or even years preceding migration, influenced by demographics and the migration context. The mental health effects on South Asian migrants are distinct, shaped by cultural and contextual factors (Li & Anderson, 2016). This blog explores the critical yet often overlooked pre-migration phase and its impact on the mental health of South Asian migrants, highlighting their unique psychosocial stressors.

The South Asian Psyche

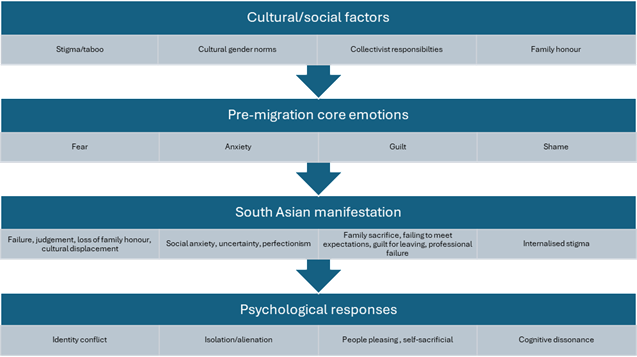

The mental health challenges faced by South Asians during pre-migration are deeply intertwined with traumatic histories and socio-cultural norms. The harrowing legacies of the caste system, colonialism and partition, continue to contribute to a fear of inferiority or failure. This cultural backdrop makes it difficult for individuals to acknowledge or express mental health concerns, often exacerbating feelings of shame, guilt, and emotional dysregulation (Sheikh et al., 2023).

The fear of being perceived as inferior or failing often prevents South Asians from seeking support, creating a cycle of generational trauma compounded by injustice, disempowerment, and unresolved trauma from historical and cultural experiences. These responses can lead to a sense of internal duality and conflict, impeding self-actualisation and identity formation as pre-migrators face the emotional weight of reshaping identity, family dynamics, and their future, often bringing unresolved trauma to the surface (Anand, 2003).

Conversely, South Asians also exhibit a strong sense of cultural resilience rooted in shared community values, spirituality, and collective identity, supporting pre-migrators to navigate challenges. This is crucial in providing a sense of empowerment to pursue economic opportunities, and forge new identities in more diverse, inclusive environments. However, beneath this sense of solidarity lies an undercurrent of unresolved trauma, societal comparisons, and cultural expectations that contribute to significant mental health challenges. While community values offer support, collectivist responsibilities and pre-migration stressors frequently exacerbate challenges (Ali, 2024; Wilson, 2006).

Pre-migration mental health stressors

Economic Pressures

The financial strain of supporting native family, alongside the substantial costs of visa fees, travel and legal expenses, can lead to anxiety and stress. Cultural expectations to succeed and send remittances coupled with economic uncertainty can lead to heightened stress long before migration begins (Wilson, 2006).

Family

Familial involvement in pre-migration decisions can significantly influence mental health outcomes, both positively and negatively. The expectation to succeed in migration is frequently tied to family reputation, placing immense pressure on individuals. Intergenerational dynamics are also crucial, as younger migrants carry the weight of elders’ hopes, whilst navigating their own desires and identity. Leaving family behind can induce profound grief, guilt, and anxiety, creating internal conflicts between the desire for personal growth and the burden of collectivist expectations. This angst coupled with anticipatory grief, can exacerbate stress, depression, and emotional instability during pre-migration. While family and community support can offer reassurance and a sense of belonging, deep-rooted expectations and pressures can contribute to feelings of guilt and inadequacy (Prabhugate, 2010).

Gendered Dimensions

Pre-migration experiences can significantly differ between genders. Female migrants may experience additional psychological stress through traditional gender roles, particularly regarding familial responsibilities. Women’s decision to migrate can be complicated by the guilt of leaving children or elderly family behind, contributing to heightened anxiety and grief, particularly when the decision to migrate clashes with deeply ingrained familial and societal expectations (Ali, 2024).

Conversely, men often bear the burden of financial responsibility. The expectation to serve as the primary breadwinner places significant pressure on men, who may worry about fulfilling their financial obligations and succeeding in a foreign country. This sense of duty, combined with the stress of migration, can lead to feelings of insecurity, anxiety, and fear of failure (Wilson, 2006).

Discrimination

Anticipating discrimination, stereotyping, judgement or exclusion in the host country can heighten anxiety, reduce self-esteem, and create an overwhelming sense of vulnerability. In particular, the rise of Islamophobia and racial discrimination intensifies these concerns, complicating pre-migration, as migrants apprehend acceptance in their new country (Li & Anderson, 2016).

Identity

South Asian migrants often experience a complex relationship with their cultural identity during pre-migration, as they navigate the balance between maintaining traditional values and adapting to a new culture. This internal conflict can be psychologically polarising, leading to identity confusion and self-doubt. The fear of losing cultural heritage or being perceived as ‘too foreign’ in either context exacerbates feelings of alienation and anxiety. This tension between preservation and adaptation can significantly contribute to poor mental health and well-being during pre-migration (Anand, 2003; Sam & Berry, 2010).

Stigma

Stigmatic cultural norms that prioritise self-sacrifice and self-reliance above seeking mental health support are a significant barrier to psychological well-being, often leading to underreporting or dismissal of psychological issues. Cultural attitudes that prioritise family honour can prevent individuals from acknowledging mental health struggles, leading to feelings of shame and exacerbating psychopathologies during transitional periods (Anand, 2003; Wilson, 2006).

Policies

The complexity and unpredictability of immigration processes and policies, coupled with inaccessible, unclear information, can foster a sense of helplessness and anxiety. Navigating the uncertainty of visa approvals, delays, or potential rejections, can lead to a pervasive fear about the viability of migration plans. This lack of control over critical aspects of migration can contribute to increased cognitive and psychological strain, manifesting as anxiety, frustration, and a diminished sense of self-efficacy (Rayp et al., 2017).

Pre-Departure Interventions

Proactive interventions can provide mental health and stress management education to reduce stigma, encourage early help-seeking, and prepare migrants for challenges such as acculturation and potential discrimination (Anand, 2003).

Cultural Sensitivity

Culturally sensitive programs that acknowledge the importance of family, spirituality, and community values are more likely to resonate with South Asian migrants, offering emotional relief, and providing strategies for coping with the challenges of pre-migration. Integrating family-centred approaches and spiritual practices with mental health support can offer comfort and a sense of continuity, fostering trust, reducing stigma, and improving migration outcomes (Mukherjee, 2024).

Community

Community networks play a vital role in providing emotional and practical support during pre-migration. Peer support networks offer opportunities to share experiences, seek advice, and alleviate isolation, supporting migrants to feel more prepared and less alone in their journey whilst reducing stigma around mental health care. Additionally, these networks can provide valuable information about the migration process, easing anxieties about the unknown (Shah et al., 2023).

Policy guidelines

- Longitudinal monitoring

Establish programs that track the mental health of South Asian migrants longitudinally, including pre-migration stressors and their evolving impact.

- Pre-migration factors

Ensure mental health assessments for migrants include consideration of pre-migration stressors to inform targeted support.

- Culturally sensitivity

Develop and fund appropriate mental health interventions, with an emphasis on culturally competent care and community-based support systems.

- Comprehensive support

Design policies that provide continuous mental health support throughout the entire migration process, acknowledging pre-migration as a critical period of stressors.

Conclusion

The pre-migration stage is an emotionally charged and often overlooked phase that significantly impacts the mental health of South Asian migrants. Migrants can face the intersectionality of economic pressures, cultural expectations, gendered stressors, and the emotional toll of separation and internal conflict leading to heightened anxiety and stress. Cultural stigma surrounding mental health often prevents migrants from seeking support, exacerbating psychological distress.

While resilience within South Asian communities through family support, spirituality/religiosity, and collective solidarity provides some emotional relief, these coping mechanisms may not fully address underlying psychopathologies. It is, therefore, crucial for pre-departure interventions to be culturally sensitive and comprehensive, offering migrants the tools required to navigate the psychological complexities of pre-migration.

References

Ali, N. (2024). Older South Asian migrant women’s experiences of ageing in the UK. Palgrave McMillan.

Anand, A. (2003). Positioning shame in the relationship between acculturation/cultural identity and psychological distress, specifically depression, among British South Asian women. [PhD thesis, University of Leicester].

Li, M. and Anderson, J. G. (2015). Pre-migration trauma exposure and psychological distress for Asian American immigrants: Linking the pre- and post-migration contexts. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 18(4), 728-739. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-015-0257-2

Mukherjee, D. (2024). Promising, culturally sensitive evidence-based interventions for Asian Americans. Oxford Academic, 296-310. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197672242.003.0016

Prabhughate, A. S. (2010). South Asian immigrants’ mental health. [Doctoral thesis, University of Illinois].

Rayp, G., Ruyssen, I., & Standaert, S. (2017). Measuring and explaining cross-country immigration policies. World Development, 95, 141-163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.02.026

Sam, D. L. and Berry, J. W. (2010). Acculturation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(4), 472-481. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610373075

Shah, M. H., Roy, S., & Ahluwalia, A. (2023). Time to address the mental health challenges of the south Asian diaspora. The Lancet Psychiatry, 10(6), 381-382. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(23)00144-x

Shaikh, M., Fatima, Z., Sharif, H. S., & O’Driscoll, C. (2023). Expressed emotion and wellbeing in south Asian heritage families living in the UK. Current Psychology, 43(10), 8852-8860. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04937-y

Wilson, A. (2006). Dreams, questions, struggles: South Asian women in Britain. Pluto Press.