Scholars have pointed out different factors for ineffective/deficient Public Policy formulation and implementation in the third world countries. Merilee S. Grindle is of the opinion that most developing countries tend to overreach when determining their priorities and making efforts to achieve good governance. They make plans for the implementation of which their institutions lack the requisite capacity. (Grindle, 2004: 526)

While this and similar explanations do carry weight, when we look at a region as contiguous and populous as South Asia (inhabiting 25.29% of the total world population as of 3rd September, 2024), we can’t help feeling that there must be a common thread or at least interrelated factors to explain the lack of good governance, and general and widespread dissatisfaction among the masses inhabiting this region.

Two indices, the Human Development Index and the World Happiness Index, amply illustrate that Public Policy formulation and implementation leave much to be desired in the countries constituting South Asia.

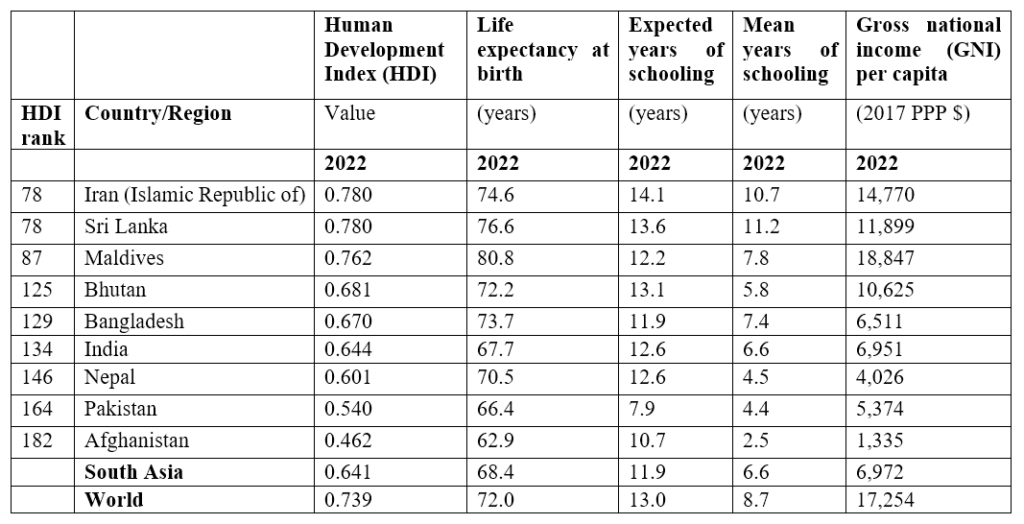

Table 1. Human Development Index and its components for South Asia (2022)

While no South Asian country scores Very Highly (≥0.800) on the Human Development Index, only Iran and Sri Lanka fare in the High (0.700 – 0.799) category. Pakistan and Afghanistan have Low (<0.550) Human Development, and all the rest are in the Medium (0.550 – 0.699) HDI category. And these are 2022 scores. Sri Lanka’s economic crisis (which had been brewing over some years) hit hard in that same year, making it fail to make a payment on its foreign debt for the first time in May, 2022, following sky-rocketing inflation, fuel shortages, closure of schools and mass protests (https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-61028138). We wonder if Sri Lanka would still be in the High HDI category when the next scores are out.

Moreover, all South Asian countries rank among the bottom 50 countries on the World Happiness Index (2024), with Afghanistan featuring at the very end (143rd). The highest that a South Asian country ranks there, Nepal, is 93rd.

A country’s Human Development Index value takes into account a number of across-the-board factors including, but not limited to, life expectancy, literacy rate, GDP per capita, rural populations’ access to electricity, and multidimensional poverty index. Similarly, the World Happiness Index makes use of observed data on six variables: GDP per capita, social support, healthy life expectancy, freedom, generosity, and corruption. All of these are areas which stand to benefit from robust public service delivery consequent upon effective Public Policy formulation and implementation. Therefore, these two indices led our research to the identification of factors across South Asia which rendered public service delivery ineffective and the government machinery prone to corruption. The search for those factors focused primarily on that arm of the state which constitutes the state’s administrative apparatus, and is tasked with Public Policy formulation and implementation – the bureaucracy. And one such factor which resonates throughout the region is the politicization of bureaucracy.

The Civil Service structure of most of the South Asian countries (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka) is derived from the two hundred years long colonial experience, which incentivized loyalty to the crown more than the loyalty to the masses. While there are other socio-political factors leading to the politicization of bureaucracy in South Asia as well, it can be said that it is this factor of colonial legacy which makes the civil servant look towards the political masters for benevolence, and enhanced perks and privileges.

Also, in the case of Pakistan and Bangladesh, the non-democratic interludes of military rules have meant that the civilian political forces did not find enough continuity of civilian supremacy to mature, leaving a void which catapulted the bureaucracy, alongside the military, to the center stage of not only public policy implementation but also its formulation. The Bangladeshi bureaucracy is further accused of following the “Pakistani tradition of involvement in power politics” (Haque, 1995).

In India, the rise of ultra-nationalist populism in the past decade has exacerbated the problem of politicization of bureaucracy, to the extent that now the civil servants are obliged not only to implement the policies of the government, but also to act as “rath prabharis” as part of a campaign to showcase the central government’s achievements.

In Nepal, even after the restoration of democracy in 1990, the elected representatives kept up the tradition of politicization of a bureaucracy already steeped in the notion of loyalty to the King in the past (Rahman, 2017).

The case of Iran is different. Public administration in the Islamic Republic of Iran is constantly striving to strike a balance between religious principles and democratic values. Here, the politicization of bureaucracy can be traced to the Iranian revolution of 1979 and not to any colonial legacy. During the initial years after the revolution, there were attempts to implement modern Western administrative concepts in Iran, but gradually the Islamic revolutionary spirit dominated (Akbari 2001; Bagherzadeh 2006; Afzali 2007; Savory 2007), which ensured that bureaucracy was managed and dominated by Islamic-values-driven officials.

Politicization of bureaucracy entails that ‘party loyalty’ is considered the main criterion for promotions, postings and transfers of civil servants (Panday, 2012). Because of compromised neutrality and impartiality of the civil servant, this politicization results in the casualty of Nolan Principles (Selflessness, Integrity, Objectivity, Accountability, Openness, Honesty and Leadership), devised by the Committee of Standards in Public Life (CSPL) in 1995 under its original chair, Lord Nolan. This leads to apathetic, inefficient and weakened institutions. Corruption is merely a manifestation of weak institutions.

Simultaneously, the politicization of bureaucracy is detrimental to the notion of Separation of Powers between the state institutions – the Executive, the Judiciary and the legislature – which is one of the basic pillars on which the edifice of democracy is erected. No democratic system can be expected to mature and evolve proper checks and balances for efficient functioning of the various state institutions, if the notion of Separation of Powers is violated, or sacrificed at the altar of political expediency.

With a bureaucracy having lost its guiding (Nolan) Principles, and with serious threats to the ideal of participative democracy, it is no wonder then that the South Asian countries are faring poorly on Human Development and Human Happiness indices.

References

- Afzali, Rasoul. 2007. Modern State in Iran: What is the Modern State [in Persian].: Mofid University Press.

- Akbari, Mohammadreza. 2001. Insiders and Outsiders [in Persian].: Payam Azadi Publications.

- Bagherzadeh, Mohammad. 2006. “Origin of Legitimacy in the Islamic Republic State [in Persian]”. Journal of Ma’refat, no. 12, 59–73.

- Grindle, Merilee S. (2004). Good Enough Governance: Poverty Reduction and Reform in Developing Countries. Governance 17 (4): 525-548.

- Haque, Ahmed S. (1995), The Impact of Colonialism: Thoughts on Politics and Governance in Bangladesh. Paper presented at the Fourth Commonwealth and post-Colonial Studies Conference, Georgia Southern University.

- Panday, Pranab Kumar (2012). Politicisation of bureaucracy and its consequences, The Daily Star. https://www.thedailystar.net/news-detail-235102, retrieved on 28 March, 2019.

- Rahman, Muhammad Sayadur (2017). Politics & Administration in South Asia: A Study of Politicization of Bureaucracy, New York: Nova Science Publishers.

- Savory, Roger. 2007. Iran under the Safavids. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press.

Table of Contents

Toggle