Any form of individual or group’s imagination that is new, novel, and unique and is traded in the market in a way that creates wealth and employment can be termed as a creative industry. However, in detail, creative goods according to United Nations Trade and Development (UNCTAD, n.d.) are films, books, paintings, artefacts, handicrafts, and many more. When these goods are traded in the market, it creates a creative industry.

Potential and Projection of the Creative Industry:

The creative industry is a relatively less explored industry that contributes around 2 trillion dollars to the global economy and employs almost 50 million people worldwide, according to the International Finance Corporation of World Bank (IFC, n.d.). In addition, it is projected that the creative sector will account for 10 percent of the global GDP by 2030, which speaks for the fast growth of this sector. These facts point toward the importance of the creative industry in economic growth. Not only this, the creative sector also leads to spillover in other industries which stems innovation, economic growth, and development.

South Asia, home to about 2 billion people with diverse history has nurtured a variegated art and culture in every aspect. This highlights the potential South Asian countries have for creative production and exports to the rest of the world which is untapped at large. Here, we overview the state of creative exports in the countries of this region over time and explore the challenges that bring the potential of the creative industry to a standstill.

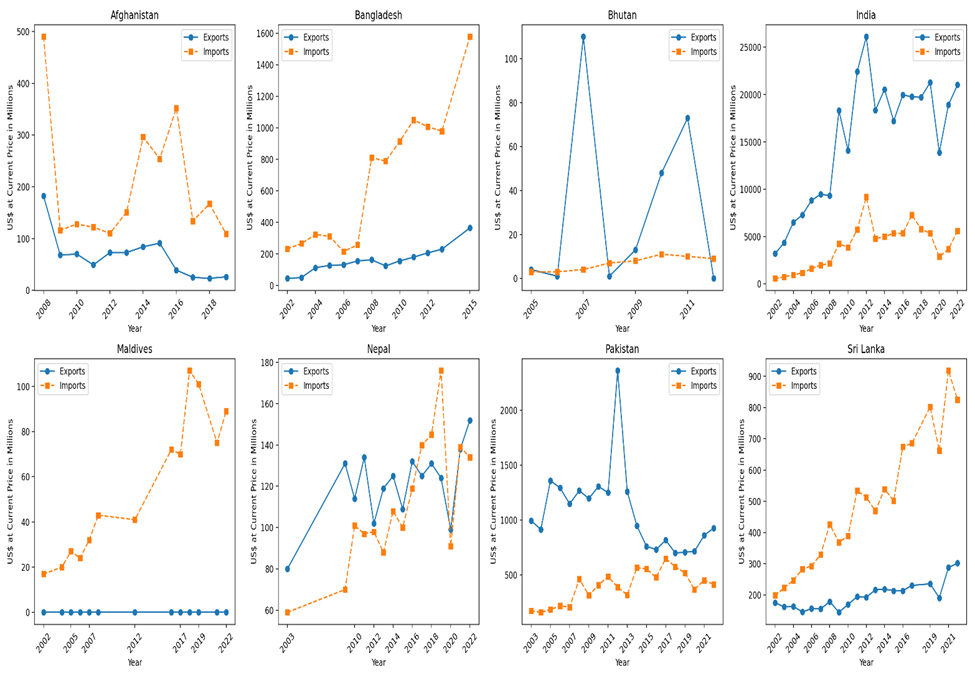

South Asian countries, in general, are moving at different paths and paces in the creative industry. However, India and Pakistan have different features when it comes to creative exports. Data on exports of creative goods from UNCTDA, for all South Asian economies, explains the situation very well and that is quite disappointing: Only India performed well, followed by Pakistan, in exports of creative goods. For instance, the data (Figure 1) of exports and imports of creative goods (US$ at current price in millions) for the period from 2003 to 2022, shows that most of the countries import creative goods more than they export. Pakistan and India are on a positive trajectory; however, that does not translate into their full potential. This is because when we examine the data on the average annual growth rate of exports and imports of creative goods, the situation is somewhat different from the one shown in Figure 1.

Figure: 1: Trade of Creative Industry in South Asia (million USD at current prices)

Analysis of the Average Annual Growth Rate in Exports and Imports of Creative Goods:

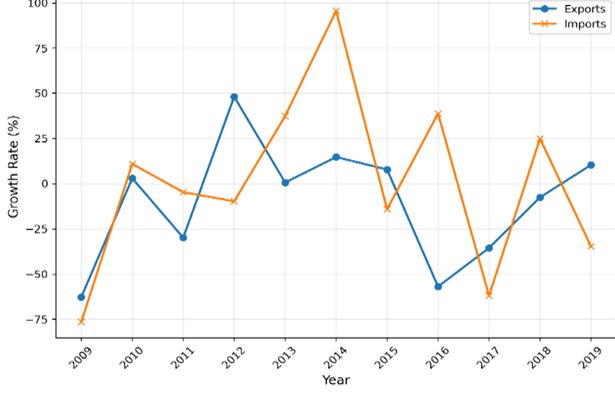

Afghanistan:

The analysis of the average annual growth rate of imports and exports of creative goods in Afghanistan shows an interesting trajectory. Afghanistan’s average annual growth in exports of creative goods remained negative for most of the years (as shown in Figure 2) and the import growth rate remained positive for various years. However, in 2019 the average annual growth rate of exports turned positive, slightly above zero and the average annual growth rate of imports of creative goods started declining and turned negative.

Given Afghanistan’s challenges and instability during the previous decades, the positive shift in its average annual growth rate of creative goods exports seems surprising. This could have happened due to multiple factors but two are important: its strengthened trade ties with India through Chabahar Port in Iran that provided Afghanistan with a stable alternate route to reach the Indian market. In addition, the peace talks with the US would also have created positive market sentiment.

Figure 2: Average Annual Growth Rate of Trade in Creative Goods for Afghanistan

Bangladesh:

For Bangladesh, data is available for the years from 2003 to 2013. It shows that the creative industry is not performing very well. The average annual growth of creative exports showed a positive jump in 2004 but began to decrease soon after hitting a negative point in 2009, and started recovering in 2010 but the curve began to flatten and hover closer to zero till 2013. In the case of imports, the average annual growth rate reached its maximum in 2008 and dropped in 2009, then turned negative in 2012, and showed an insignificant recovery in 2013 (see Figure 3). During the period of 2009 to 2013, Bangladesh’s policy was focused on enhancing exports. Despite having a centred policy, Bangladesh’s growth rate of creative goods could not adopt an upward trajectory. Including other factors, this could also be the result of continuous country-wide strikes, instability and the Eurozone crisis, that occurred between 2010 and 2012.

Figure 3: Average Annual Growth Rate of Creative Goods Trade for Bangladesh

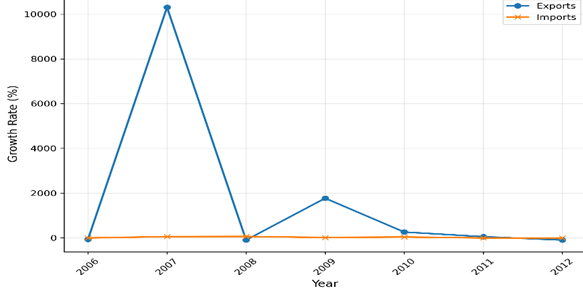

Bhutan:

Data on Bhutan’s average annual growth rate of exports and imports of creative goods is available only from 2006 to 2012. The data shows that during these years, the average annual growth rate of exports was negative in 2006, but showed a jump of thousands in 2007, turned negative in 2008, showed recovery in 2009 but started declining and went below zero in 2012. During this period, the growth rate on imports remained closer to zero and did not show much movement. A huge jump in 2007 could be the result of the low initial base in 2006. And then a subsequent decline could also be the result of the global financial crisis in 2008 that reduced the demand for non-essential goods, including creative goods from smaller exporters like Bhutan.

Figure 4: Average Annual Growth Rate of Creative Goods Trade for Bhutan

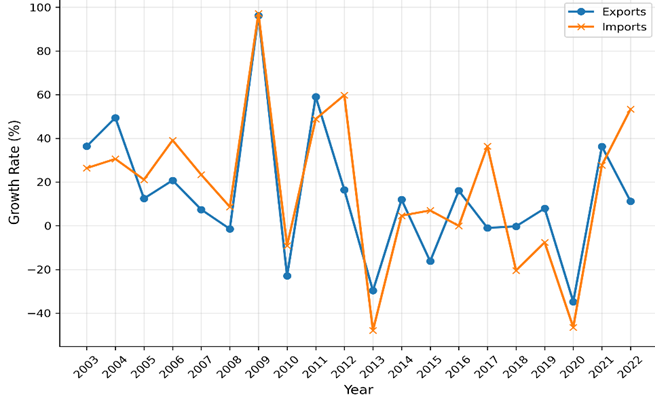

India:

India is the largest South Asian economy with a billion-dollar creative industry, especially the cinema industry. However, there is now a constant positive growth trajectory of its creative exports. There are continuous negative dips in the average annual growth rate of creative exports. The average annual growth rate of creative imports and exports have almost similar trajectories, such as both exports and imports growth being highest in 2009, as shown in Figure 5. However, the path is different in 2022, the growth rate of imports is increasing whereas the exports’ growth rate is falling towards zero. The peak in 2009 could be the likely result of post-crisis recovery. And then the divergence in 2022, including other factors, is likely due to the persisting effect of COVID-19.

Figure 5: Average Annual Growth Rate of Creative Goods Trade for India

Maldives:

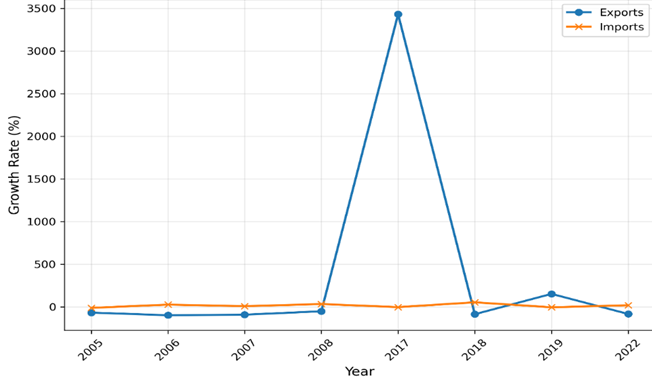

Data on Maldives’ average annual growth of imports and exports of creative goods is available only for a few years from 2005 to 2022 (Figure 7). The chart below shows a quite not-so-good picture as there is only one positive jump in growth of exports in 2017, that is in thousands per cent. For the rest of the years, both exports and imports moved along zero with positive and negative trends. However, in 2022 export growth rate is negative whereas import growth is showing a positive trend.

As Maldives is a heavily import-dependent country to meet domestic demand, therefore, the positive average annual growth rate of creative imports could be the result of the post-pandemic recovery.

Figure 6: Average Annual Growth Rate of Creative Goods Trade for Maldives

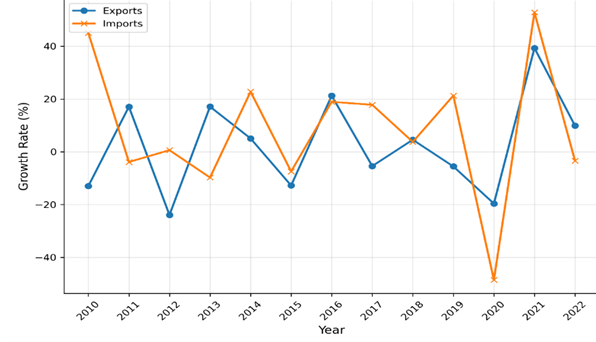

Nepal:

Nepal had a positive import growth rate in 2010 and a negative growth rate of exports of creative goods during the same years. However, as Figure 8 shows, the imports’ growth rate turned negative in 2011 and the exports’ growth rate turned positive. There has been a continuous trend of positive and negative cycles of import and export growth rate, and in 2021 both exports and imports growth peaked and in 2022 started falling, and the trend is downward sloping. The peak in 2021 could likely be the result of a post-pandemic rebound, but the subsequent decline in 2022 shows Nepal’s creative industry lacks the capacity to sustain the growth of exports.

Figure 7: Average Annual Growth Rate of Creative Goods Trade for Nepal

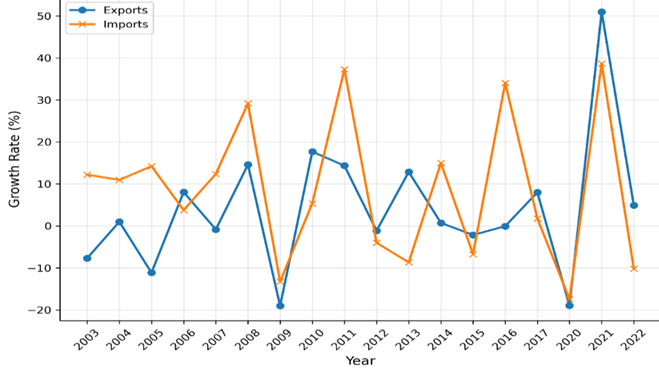

Pakistan:

Despite having a vibrant creative industry, Pakistan has not shown a continuous positive trend in the average annual growth rate of exports of creative goods: for one year it is positive and negative for the next year and this trend is continuous from 2004 to 2022 as represented in Figure 9. In 2021, both the imports and exports growth rate was upward slopping but started falling in 2022. The export growth rate is positive but falling, whereas the import growth rate is negative in 2022.

The peak Pakistan achieved in 2021 is likely the result of post-pandemic global recovery that surged the overall demand, including the demand for creative goods. However, the negative trend in 2022, could be explained by the backdrop of the political instability in Pakistan, Pakistan’s restrictions on imports to manage the current account deficit, and the surge in the cost of production.

Figure 8: Average Annual Growth Rate of Creative Goods Trade for Pakistan

Sri Lanka:

Like the rest of the South Asian economies, Sri Lanka has also not shown steady growth in exports of creative goods. The data on Sri Lanka is available between 2003 and 2022. The growth rate of imports of creative goods remained positive for most of the years whereas the growth rate of exports remained negative. However, in 2021 both imports and exports’ growth peaked and exports’ growth surpassed the imports. But both began to decline and the growth rate of imports turned negative and the exports’ growth rate is positive but falling, as we can see in Figure 10. Like all other countries, Sri Lanka also showed recovery after the pandemic but could not sustain the growth in the subsequent year.

Figure 9: Average Annual Growth Rate of Creative Goods Trade for Sri Lanka

Although the subject under discussion requires in-depth empirical investigations to fully understand the cause and effect, this overview concludes with many useful insights from the data on imports and exports of creative goods by all the South Asian economies. For instance, it suggests that all the countries are not operating at their full potential when it comes to the creative industry. From the historical data trends, it is evident that all of the South Asian countries have a negative trend in the average annual growth rate of exports of creative goods. The data shows that almost all the countries showed recovery after the pandemic, but no economy could sustain the growth for even the next few years. This trend hints towards something going wrong with the creative industry of these economies that need the attention of the policymakers.

Keeping in view these insights, a few basic but important challenges faced by the creative industry of South Asian countries that are hindering it from achieving its full potential are discussed here.

Challenges Faced by the Creative Industry in South Asia

Push and Pull Factors:

Since the data under observation is about creative exports, we also need to look at the push and pull factors for exports. Salim & MAHMOOD (2015) explain the determinants of cultural exports in Pakistan and explain that GDP growth positively influences the exports of cultural goods, and most importantly, common language and colonial ties with the trade partners also positively impact the exports of cultural goods.

In addition, when we look at Pakistan and India’s relations, they have been bitter since partition. Both countries have a general ban on imports and exports with each other including cultural goods. This is counterproductive for both countries, since they are already exporting less than their potential due to certain reasons, such as not having a common language, and most of the films for instance are produced in local languages in both countries which makes them less attractive for the western native audience.

The same is the case for the rest of the South Asian countries. There are few regional ties, and that hampers regional trade. All the countries mostly produce creative content, e.g. films, books, etc., in local languages, which leaves little room for exports. Therefore, each country has to work on push and pull factors to enhance the possibilities of exporting creative goods: That includes promoting the production of creative goods (films, books) in foreign languages through investment in the creative industry and attracting foreign direct investment. Second, it includes reducing restrictions on regional trade.

Access to the International Digital Marketplaces:

Creative exports also include artefacts, books, and other crafts, which are also created by artists living in far-off areas of a country. These artists need a subtle and easy route to reach domestic and international markets. However, all of the South Asian countries lack in this context. For instance, Amazon, a giant global marketplace, is not available in any South Asian country except India. Therefore, it is recommended for all these economies to make such marketplaces accessible to its craftsmen, and people in general. So that these artists can present their products to the international audience or customers with ease and dignity.

Lack of Environment Conducive to the Creativity:

The creative industry is logically based on the creativity of an individual, group community, or nation in this case. Creativity flourishes in an environment that is open encouraging, and tolerant towards new ideas (Florida, 2002). When ideas are censored and compelled to be aligned with a certain ideology or policy, the outcome becomes monotonous and ceases to expand.

This very basic understanding of creativity says that people should be provided with political and civil freedoms for creativity and then innovation to take place. However, the Freedom House Index, reports Pakistan as a partly free country, whereas, Afghanistan is not a free country. India is also suggested as partly free, however, it scores high on both the political rights and civil liberties index in the region. In short, no South Asian country is ranked as fully free on the Freedom House Index, however, India stands in a better position with high political rights and civil liberty scores.

These scores explain that these economies lack an environment conducive to creativity and innovative spillovers. As Najam et al. (2023) explain in the case of Pakistan lesser civil liberties have a negative association with innovation, and lesser freedoms constrict ideas to be born and move freely to meet and mate with each other.

Films and books are often banned in these countries. All these countries, especially India and Pakistan ban each other’s films from being screened in each other’s countries. And it does not stop here, rather many other soft creative outputs are either banned, disliked, or discouraged by the states.

What this means is not just a ban on a single movie or a book, rather it first shrinks the possibility of dissemination of an idea, free flow of an idea, and it blocks its chances to meet with other ideas. Second, the ban on a book or a film means depriving people of the economic activity that a particular book, film, or any other creative good would have created. So it has both vertical and horizontal effects.

Policy Recommendations:

There is a need to formulate a policy that makes the environment conducive to creativity; at the policy level, attention must be paid to tolerance and openness. The countries should work to increase the pool of creative classes through investment in education and skill development. Strengthen the regional ties, and facilitate the trade of creative goods with neighboring countries.

The laws against piracy and copyrights should be strengthened, as it is the foundation of the sustainability of the creative industry. This is because the availability of pirated versions of movies, books, or any other art is a monetary loss to an artist. It also discourages international investment in the creative industry. Therefore, strengthening and implementing the laws against piracy, copyright violations, and intellectual property rights violations is necessary as these violations are rampant in South Asia.

A comprehensive policy should be formed to uplift the local artists and artisans living in far-off areas of the countries and to provide them with access to international markets through different digital marketplaces.

References

Florida, R. (2002). The Rise of Creative Class. New York: Basic Books.

IFC. (n.d.). https://www.ifc.org/en/what-we-do/sector-expertise/creative-industries. Retrieved from https://www.ifc.org/en/home.

Najam, A. A., NAEEM, M. Z., RAMONA, B., & VALERIU, N. P. (2023). INVESTIGATING THE IMPACT OF CIVIL LIBERTIES AND CREATIVE CLASS ON. Annals of the „Constantin Brâncuşi” University of Târgu Jiu, Economy Series(3).

Salim, S., & MAHMOOD, Z. (2015, July-December). Factors Shaping Exports of Cultural Goods from Pakistan. NUST JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES, 1, 73-86.

UNCTAD. (n.d.). Documentation. Retrieved from https://unctadstat.unctad.org/.

Data Source: https://unctadstat.unctad.org/datacentre/

Table of Contents

Toggle