Education is a cornerstone of a nation’s development, influencing economic growth, social stability, and overall human well-being. While South Asian countries have made strides in education, significant challenges remain in terms of access, quality, and equity. In 2022 the total adult literacy rate in South Asia was 74% which is a major jump from 2000 when the rate was 58%. Gender-wise disaggregation shows that this rate for females is 67% and males is 82% for 2022. Thus there is a wide gender disparity in terms of literacy. This analysis discusses the state of education in South Asian countries with an objective of identifying key challenges and proposing potential solutions.

Pakistan

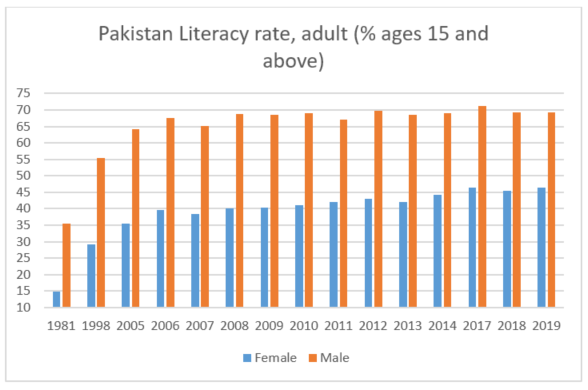

In Pakistan, the education sector faces significant challenges, despite various efforts by the government, non-governmental organizations, and international agencies. While there have been pockets of progress, the broader picture reveals a sector struggling to meet the needs of its population, particularly in terms of access, quality, and equity. In 1959 the government launched the National Education Commission and the first National Education Policy was formulated in 1970. These efforts led to a significant increase in enrollment rates, particularly at the primary level. However, the quality of education remained a major concern, with high dropout rates and low literacy levels. According to the Pakistan Economic Survey 2023-24, the country’s literacy rate stands at 62.8%, with significant disparities between urban and rural areas, as well as between genders. The Pakistan Bureau of Statistics gives the literacy rate in urban areas to be around 77.3%, while in rural areas, it is at 54.1%. Gender disparities are also stark, with male literacy at 73.4% compared to 51.9% for females. Besides this, Pakistan’s education system is characterized by a complex and often fragmented structure. It consists of public and private schools, madrasas, and a range of vocational and technical institutions.

Over the years, successive governments in Pakistan have launched various initiatives aimed at improving the education sector. The National Education Policy 2017, for example, set ambitious targets for increasing enrollment, reducing dropout rates, and improving the quality of education. The policy emphasized the need for curriculum reform, teacher training, and the use of technology in education.

The introduction of the Single National Curriculum (SNC) in 2021 was another significant step, aimed at reducing disparities between public and private schools and promoting national cohesion. The SNC seeks to provide a uniform curriculum across all schools, with a focus on critical thinking, creativity, and character building. However, the implementation of the SNC has faced criticism, particularly regarding the pace of its rollout and concerns about the quality of content.

In recent years, the government has also increased its focus on technical and vocational education and training (TVET). Recognizing the need for a skilled workforce to drive economic growth, various programs have been introduced to enhance the quality and relevance of TVET. These include public-private partnerships, curriculum updates, and the establishment of new training centres. However, challenges remain in ensuring that TVET programs align with market needs and are accessible to all segments of the population.

India

India has made significant progress in education, with increased enrollment rates and improved literacy levels. However, challenges persist, including disparities between rural and urban areas, gender disparities, and the quality of education. India has also implemented national curriculum frameworks to improve standardization and quality. Government initiatives and improved educational infrastructure in India have played a crucial role in reducing dropout rates across all levels of education.

The Samagra Shiksha Scheme and Swachh Bharat Mission (2014) have prioritized sanitation and water access, ensuring that these essential resources are available in most government schools. Alongside, the RTE Act (2009), and other initiatives like free textbooks, uniforms, and the Midday Meal Scheme coupled with investments in school facilities, residential hostels, and teacher training, have made education more accessible and engaging for students. These combined efforts have not only increased enrollment but have also fostered a more inclusive and equitable educational environment for both boys and girls in India. Schools witnessed notable improvements in amenities such as toilets for both girls and boys, drinking water, and hand-washing facilities.

Additionally, the ICT component of the Samagra Shiksha Scheme has supported the integration of technology into education, with the establishment of smart classrooms and ICT labs equipped with hardware, software, and e-content. These advancements have created a more conducive learning environment for students across the country. The Indian government has initiated the PM Schools for Rising India (PM SHRI) scheme on 7 September 2022, to establish and upgrade over 14,500 schools across the country. These schools will be equipped with modern infrastructure and implement the National Education Policy (NEP), serving as models for other schools in their communities. The scheme aims to benefit more than 2 million students (Indian Ministry of Finance). However, like Pakistan, in India too, the quality of education in public schools is compromised, necessitating non-conventional educational approaches to meet contemporary needs, including personal development programs and employment-based learning.

Bangladesh

Bangladesh has made substantial advancements in its education sector, particularly at the primary level. This progress is evident in the significant increase in enrollment rates and notable improvements in literacy levels, especially among women. The government’s commitment to making education accessible and affordable has been instrumental in driving these positive outcomes. According to the UNESCO Institute of Statistics, Bangladesh achieved a primary net enrollment rate of 97% in 2021, indicating significant progress in ensuring that children have access to primary education. Additionally, the country’s adult literacy rate increased from 56% in 2000 to 76% in 2021 (World Development Indicators), reflecting the positive impact of education initiatives. However, challenges persist in secondary and higher education, including disparities in access and quality. Access to these levels of education remains limited for many, especially in rural areas and marginalized communities. Furthermore, the quality of education, particularly in public institutions, varies significantly. Dropout rates at the secondary and higher levels remain relatively high, indicating a need for interventions to improve retention.

To address these challenges, the Bangladeshi government has implemented various initiatives, including the National Education Policy (NEP) 2010. The policy was formulated by a committee chaired by National Professor Kabir Chowdhury and co-chaired by eminent economist Dr. Qazi Kholiquzzaman Ahmad and outlines 30 aims, objectives, goals, and principles for education. The NEP 2010 builds upon previous education reports, such as the Qudrat-E-Khuda Commission Report, which recommended extending primary education to the eighth grade, introducing pre-primary education, and emphasizing vocational/technical education. While the NEP shares many common goals with these earlier reports, it differs in its approach and commitment to implementation.

However, the NEP lacks a coordinated and comprehensive approach for successful implementation. Isolated actions, such as not linking NEP decisions to broader government policies, have hindered progress. Allocating adequate funds for education has been a persistent challenge. The government has often struggled to meet the financial demands of implementing the NEP’s ambitious plans. Even with the available funds, there have been concerns about the efficient use of resources, including infrastructure development, teacher training, and curriculum development. Implementing a decentralized education system has faced obstacles, such as resistance from local authorities and a lack of capacity at the grassroots level. Ensuring accountability and transparency in the education sector has been a challenge, with concerns about corruption and mismanagement. Ensuring that the curriculum is relevant, updated, and aligned with the needs of the 21st century has been another area of concern.

Nepal

Nepal has made significant strides in its education system, particularly in terms of access and quality. The first comprehensive curriculum framework for Nepal’s school education was launched in 2007 and the first curriculum framework after Nepal changed to a federal state was launched in 2019 (Poudel, Jackson, & Choi, 2022). The adult literacy rate is 71% (2021) according to the World Development Indicators. According to the UNICEF 2019 report, 82% of children complete lower basic schooling. However, only 27% of children complete secondary school while 15% of secondary school-age children are out-of-school. Although the Constitution of Nepal guarantees free and compulsory education up to the upper basic level and free education through secondary school. The average net attendance rate for early childhood education is 62%.

The implementation of the new Education Act in 2016 has been a key development in improving the literacy rate as well as the quality of education. This act aims to create a learner-centred education system that emphasizes critical thinking, problem-solving, and innovation. The government has also focused on improving teaching and learning by providing teacher training and support and establishing national standards for teacher qualifications. Programs like free primary education and the establishment of community schools have led to a significant increase in enrollment rates. Despite these improvements, Nepal’s education system still faces challenges. Infrastructure, particularly in rural areas, remains inadequate, deterring students from attending school. There’s a shortage of qualified teachers, especially in subjects like science, mathematics, and English. Discrimination based on caste and class has limited the educational opportunities for marginalized groups. Only 33% of children from the poorest households attend secondary school in comparison to 68% of children from the richest households.

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka has a relatively well-developed education system, with high literacy rates and good access to education. One of the notable features of Sri Lanka’s education system is its free education policy, which guarantees every child the right to free education up to the age of 16. This policy has helped in the population having a literacy rate of 92%, which is higher than that expected for a third-world country (Sri Lanka Ministry of Education). It has the highest literacy rate in South Asia. The government maintains a vast network of schools, including national schools, provincial schools, and pirivenas (monastic colleges).

While Sri Lanka’s education system has achieved significant progress, it faces several challenges. One of the key issues is the quality of education, particularly in rural areas. There is a significant disparity in resources and facilities between urban and rural schools. The student-to-teacher ratio in urban areas is 19:1 compared to 29:1 in rural regions. Some rural schools lack basic infrastructure, teaching materials, and access to technology, which can affect the quality of education provided. Public expenditure on education is low at 1.9% of GDP (2020), which hinders investments in infrastructure and research at universities.

Another challenge facing Sri Lanka’s education system is the increasing emphasis on English language education. While English proficiency is essential for many career paths, it can also create disparities for students who are not fluent in the language. The government has taken steps to improve English language education, but more needs to be done to ensure that all students have equal opportunities to learn the language. In recent years, there has been a growing focus on vocational and technical education in Sri Lanka. The government has established vocational training centres and apprenticeship programs to equip students with practical skills for the job market.

Things to learn from Sri Lanka. Some strategies that have worked

Analyses of the education system in all these countries show that they have similar challenges which include disparities in access to education exist in all South Asian countries, particularly in rural areas, among marginalized communities, and for girls. The quality of education varies significantly across South Asian countries, with challenges in terms of infrastructure, teacher qualifications, and curriculum relevance. Gender disparities and disparities between rural and urban areas persist in all South Asian countries. Although the comparison of the literacy rates in the youth population of all the South Asian countries shows that Sri Lanka is performing very well and the rest of the countries except Pakistan are catching up, but the quality of education needs to be assessed. Curricula often do not align with current job market demands, leading to a mismatch between skills and employment opportunities. Each government needs to address this issue to increase the employability of the youth.

Other Asian countries can learn from the lessons of the efforts made by Sri Lanka in markedly increasing its literacy rate. This was mainly possible due to 1945 Universal Free Education Policy that ensured free education from kindergarten to university level. To support this initiative free mid-day meals were also provided which helped enhance school enrollment especially for the poor (Liyanage, 2014). These initiatives were possible by allocating 4% of GDP for education. In the 1990s the government introduced free school text books, uniforms and subsidized public transportation for the students. With the help of International Development Assistance Program in 1998 Sri Lanka made significant investments in educational infrastructure, including schools, libraries, and technology, to support learning. While Sri Lanka’s free education system has propelled the country to a leading position in South Asia in terms of literacy rates, school enrollment, gender parity, and human development, critics argue that its progress has stagnated. The system may not be evolving rapidly enough to meet the evolving needs of a changing world. Sri Lanka’s Central Bank reports consistently indicate a decline in budgetary allocations for the state education sector. University lecturers and other stakeholders advocate for increasing this allocation to upto 6% of GDP to ensure the quality of Sri Lanka’s free education system. This substantial increase is crucial to meet the growing demands of the education sector and prevent further deterioration in its standards (Alawattegam, 2020).

Policy Recommendations

To address these challenges, South Asian countries should increase public investments in education. Governments should allocate more resources to education, focusing on improving infrastructure, teacher training, and curriculum development. Collaboration with the private sector can expand access to education, provide industry-specific training, and improve the quality of education. Curricula should be regularly updated to align with current job market demands and promote critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity. Teacher training programs should be strengthened to ensure that teachers have the necessary skills and knowledge to deliver effective instruction. Efforts should be made to address gender disparities in education, including providing scholarships for girls and implementing gender-sensitive policies. Technology can be used to improve access to education, enhance learning outcomes, and reduce costs. Regular monitoring and evaluation of education programs are essential to identify areas for improvement and ensure that resources are being used effectively.

South Asian countries can also look at and adopt policies that have successfully worked in other countries. Brazil’s PNAIC (Pacto Nacional pela Alfabetização na Idade Certa), launched in 2012, is a successful example of a program that has significantly increased literacy rates. This program specifically targets adults who have not completed primary education. The program is implemented at the community level, making it accessible to adults who may have difficulty attending traditional schools. The PNAIC offers flexible learning options, including evening classes and weekend workshops, to accommodate the needs of working adults. The program provides specialized training for teachers who work with adult learners, ensuring that they are equipped with the necessary skills to address the unique needs of this population. It focuses on developing both literacy and numeracy skills, empowering adults to participate more fully in society and the economy. The PNAIC has been highly successful in increasing literacy rates among adults in Brazil. It has helped to improve economic opportunities for adults who were previously excluded from the workforce and has contributed to social inclusion and empowerment.

By implementing these various strategies, South Asian countries can improve the quality and accessibility of education, leading to better educational outcomes for their citizens and stronger economies. Furthermore, regional cooperation and knowledge sharing among South Asian countries can enhance the effectiveness of education reforms. By learning from each other’s experiences and best practices, countries can accelerate progress and achieve shared goals of educational excellence.

Table of Contents

Toggle